By Nick Deiuliis

Listening yet again to Billy Crystal and the rest of the geriatric New York-centric elite wax on endlessly about how great the 1950s were for baseball is exhausting. If I have to hear about Willie, Mickey, and the Duke one more time, my head is going to explode. We get it: New York City had three teams back in the day and they all had great players.

My generation knows the greatest of eras in baseball history was the 1970s and early 1980s. Epic dynasties, compelling rivalries, and memorable stars. The best time to be a fan, especially a young one, no matter where in America you called home.

Major League Baseball is the stingiest of pro sports when it comes to allowing entry into its Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Last year only one individual, manager Jim Leyland, was inducted. And there have been nine years when no players were voted in.

That leaves deserving players on the outside looking in. Most troubling are greats who made their names during the 1970s and early 1980s, and whose window for conventional induction has closed.

Blame those who never played the game but are self-anointed experts at judging those who did: journalists.

Getting into Cooperstown under the standard track requires 75% of the Baseball Writers Association of America to vote to allow it. Media can block any player for any reason. And it does.

There are five players who ruled the 1970s through much of the 1980s that deserve a second look by Cooperstown. Ones that didn’t gamble on the game (by the way, he should be in, too) and that predated the steroids era. They performed at a high level over long careers, with the five resumes ranging between 17 and 20 years.

Consider their cases and ask yourself how Cooperstown is complete without them.

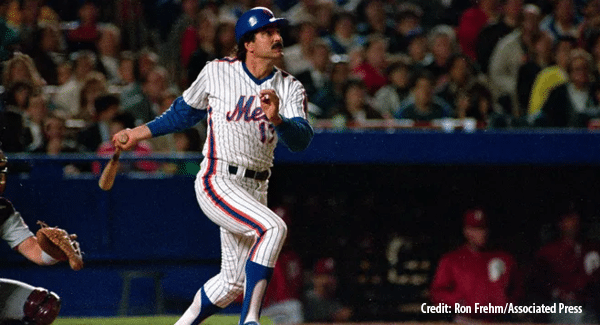

Keith Hernandez (aka The Boyfriend from Seinfeld’s 3rd season)

Hernandez clearly checks more than a few boxes for Cooperstown.

An accomplished winner over his 17-year career. Two World Series titles for two different teams, first the Cardinals and then the Mets. Batting title the same year he was league MVP (1979).

A great contact hitter, finishing just shy of the career 0.300-mark for batting average (he bested the 0.300 threshold in seven seasons). And Hernandez had a great eye in the batter’s box, amassing over 1,000 career walks at a rate of nearly 15% of at-bats. Although he only managed 200+ hits one time, he reached base 250+ times eight different seasons.

Many consider Hernandez the greatest defensive first baseman in history. He won eleven consecutive Gold Gloves at the position. He has 1,682 career assists, third all-time. He single-handedly took away the option of bunting. A player in any sport should be in its Hall of Fame if they were the greatest ever at a key aspect of the game.

Hernandez sports an impressive, Hall of Fame-worthy 60+ Wins Above Replacement (WAR) that reflects his all-around strengths and attributes.

There are two criticisms of Hernandez that contribute to him remaining on the outside of the Hall of Fame looking in. First, he lacked power expected for his position, hitting only 162 home runs over 17 seasons. Cooperstown likes first baseman noted for the long ball. Second, he was one of the players caught up in the Pittsburgh drug trials, with his cocaine use catching up to him.

But this is the National Baseball Hall of Fame, not the Clean-Living Hall of Fame. And the game of baseball consists of more than the home run. Get Hernandez in there.

Dave Parker (aka The Cobra)

During the 1970s, Dave Parker stood above everyone on the field, literally, at a towering 6 feet 5 inches tall. And weighing in at 230 pounds, Parker looming in right field or rounding the bases toward home was an intimidating sight to behold. He would warm up in the batting circle with a sledgehammer (following a practice employed by teammate Willie Stargell).

Add to his physical presence key achievements: two titles with two teams (Pirates and A’s) and a league MVP award.

The Cobra got his nickname from his coiled stance and unleashed strike from the left side of the batter’s box. He was capable of inflicting massive damage with his bat, as his two back-to-back batting titles attest. He could hit for power, amassing over 300 career home runs and nearly 1,500 RBIs, both at impressive at-bat rates. And he could hit for average, finishing with a cumulative 0.290 batting average and over 2,700 hits.

And despite his size, he had impressive speed early in his career. His over 150 stolen bases over 19 years are easily the highest of any of our five induction-worthy players.

Parker won three Gold Gloves, and base runners learned quickly to think twice before testing his arm from right field. Just watch the highlight video of his two legendary throws in the 1979 All Star Game for exemplars; throws that earned him the game’s MVP award. His defensive play tapered off drastically later in his career, but in his prime he was about as electric as it got in right field.

So, what’s keeping a player who passes the eye test out of upstate New York? Parker’s WAR is respectable, at just over 40, albeit not Hall of Fame-caliber. His relatively low walk rate might have detracted from his WAR score (by way of comparison, Hernandez amassed almost 400 more career walks despite having nearly 2,000 fewer at-bats).

Like Hernandez, Parker succumbed to drug issues during his career. He also enjoyed a level of confidence that came across to fans as arrogance, and becoming the first million dollar-a-year athlete in Pittsburgh and then under-achieving at a time when steel mills were being shuttered left and right didn’t help his image.

Fortunately, Parker rebounded from his struggles and today serves as an inspiration for those suffering from Parkinson’s disease. And anyone who had the pleasure of watching The Cobra knows Cooperstown is not complete until his name is in it.

Steve Garvey (aka Mr. Clean)

If you doubt that to be the case, consider a Sporting News poll of National League managers in 1986. Garvey came up fifth in the answer to a question about which players would deserve a Hall of Fame plaque if their careers came to an end right away. The only names in front of Garvey’s: Pete Rose, Steve Carlton, Mike Schmidt, and Nolan Ryan.

Over 19 seasons, Garvey accumulated one hit shy of 2,600 hits and finished with a career batting average of 0.294. Garvey reached the 200-hit mark in six seasons, something achieved by 13 other players in history at the time of Garvey’s retirement. All 13 are in the Hall of Fame, except for Pete Rose. And Garvey had good power, hitting home runs at an impressive per-at bat rate.

Garvey was a very solid fielder, winning four Gold Gloves at first base during an era when Keith Hernandez was stringing eleven Gold Gloves in a row at first base in the same National League.

But what makes Garvey most deserving of the Hall of Fame are his career accomplishments beyond the traditional stats. He won a title with the Dodgers in 1981, beating the hated Yankees. He was a league MVP. His playoff performances earned him National League Championship Series MVP, twice. And he was a perennial all-star, winning the MVP award for that game, twice.

But here is the most impressive accomplishment of Garvey’s that not many appreciate: he is the all-time National League iron man. Garvey sits fourth on the all-time consecutive games list, behind American Leaguers Ripken and Gehrig (and lesser-known Everett Scott), making him the National League iron man, with over 1,200 consecutive games played. That streak, spanning nine seasons, exceeds the next closest National Leaguers and legends: Billy Williams and Stan Musial.

Garvey’s career produced a WAR of only 38, below the Hall of Fame norm. A contributor was his desire as a hitter to swing away instead of taking a base on balls. In fact, Garvey has the lowest walk ratio of any of the five on this list. He placed a premium on RBIs at a time when that was the norm.

And some critics hold Garvey’s personal drama later in his career against him. Probably because it was in stark contrast to his polished image. But consider what gets ignored today: celebrated stars despite allegations of domestic-abuse, excessive philandering, and exhibiting boorish behavior toward fellow humans.

Garvey certainly wasn’t perfect off the field, but his faults were quite mild by today’s standards. His stats get him close, and his accomplishments put him over the top. Time for Cooperstown to call.

Al Oliver (aka Scoops)

This is probably the most surprising name of the five when it comes to Hall of Fame consideration. But Oliver had an incredibly impressive career that was overshadowed by bigger names on his great teams or that unfolded in ignored baseball backwaters.

He won a World Series with the 1971 Pirates. That championship team during the ’71 season would enjoy an outfield of Willie Stargell in left, Oliver in center, and Roberto Clemente in right. Talk about a field of dreams, as well as a pitcher’s nightmare.

But then Oliver was off to the Rangers and Expos. Six seasons in total. Yet moving from great lineups with the Pirates Lumber Company to lesser ones to the south and north didn’t hurt Oliver’s offensive production. It improved.

Scoops was a great contact hitter and is the only player of the five that broke the 0.300 mark for career batting average. Oliver has the most career hits of the bunch, at 2,743. His power was good. He won the league batting title in 1982 with the Expos.

Oliver is an interesting study when it comes to Hall of Fame inclusion. He wasn’t an exemplary fielder, never having won a Gold Glove. He didn’t walk enough, similar to the popular criticism of Garvey. And his WAR of just under 44 is lower than that of most players who landed in the Hall of Fame.

But there is a sadly ironic aspect about Oliver’s story that is crucial when considering his Cooperstown credentials. His career was effectively cut short due to baseball ownership colluding to keep him off a major league roster toward the end of his career (which was legally affirmed and resulted in Oliver being awarded damages). His career ended from boycott, not diminishing on-field performance.

If he was given the chance to play out his career to the extent his abilities allowed (especially as a designated hitter), it is safe to say he would have surpassed the 3,000 hit mark. Which would make him a sure-fire hall-of-famer because those with 3,000 career hits that are not in the Hall of Fame are either not yet eligible, are tainted with steroid abuse, or are named Pete Rose.

Major League Baseball’s restitution to Oliver will not be complete until he is in the Hall of Fame.

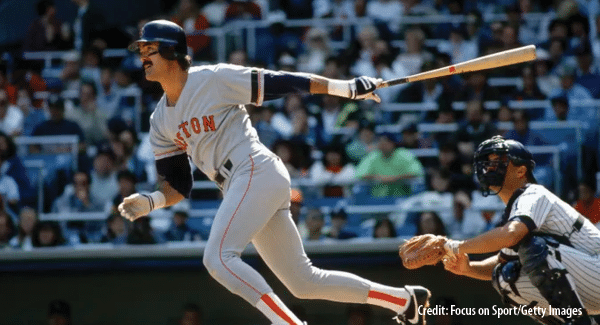

Dwight Evans (aka Dewey)

Perhaps we saved the best and most surprising for last with the case for Dwight Evans. He played on great Red Sox teams and was oft overshadowed by stars like Yaz, Rice, and Fisk. Evans spent 19 of his 20 years in the major leagues with the Red Sox; he is second on the all-time games played list for the Red Sox, surpassed only by Carl Yastrzemski.

Three attributes place Evans in the Hall of Fame discussion.

First, he had great power. His home run-per-at bat is easily the best and highest of the five up for consideration. Dave Parker is next best and is a distant second to Evans. Evans didn’t start out as a great hitter; he was viewed more as a defensive specialist who then worked himself into being a great hitter.

Second, he had a great eye as a batter and his career walks tally proves it. He accumulated nearly 1,400 career walks, at a rate rivaled only by Keith Hernandez within the group of five. Evans is an impressive combination of power and eye.

Last, he was excellent with the glove in the field. Eight career Gold Gloves don’t happen by accident or luck. His arm in rightfield was matched only by Dave Parker’s, and Parker could only do so in his prime.

All three attributes contribute to Evans’ excellent WAR of over 67, the highest of the five deserving players. That tally is beyond respectable for Hall of Fame inclusion, better than Duke Snider’s (take that, Billy Crystal!) and just a tad under Ernie Banks’.

Evans’ argument for entry to Cooperstown is simple. His case isn’t the what-if of Oliver, or the eye-test of Parker, or the resume of Garvey, or the greatest-ever at some aspect of Hernandez. He was incredibly consistent with his strengths, and those strengths over twenty years constructed a great career case.

Take all the names, videos, and awards away. Leave only the numbers. An objective baseball afficionado will look at Evans’ career stats and wonder how such a player is not in the Hall of Fame. The answer remains elusive.